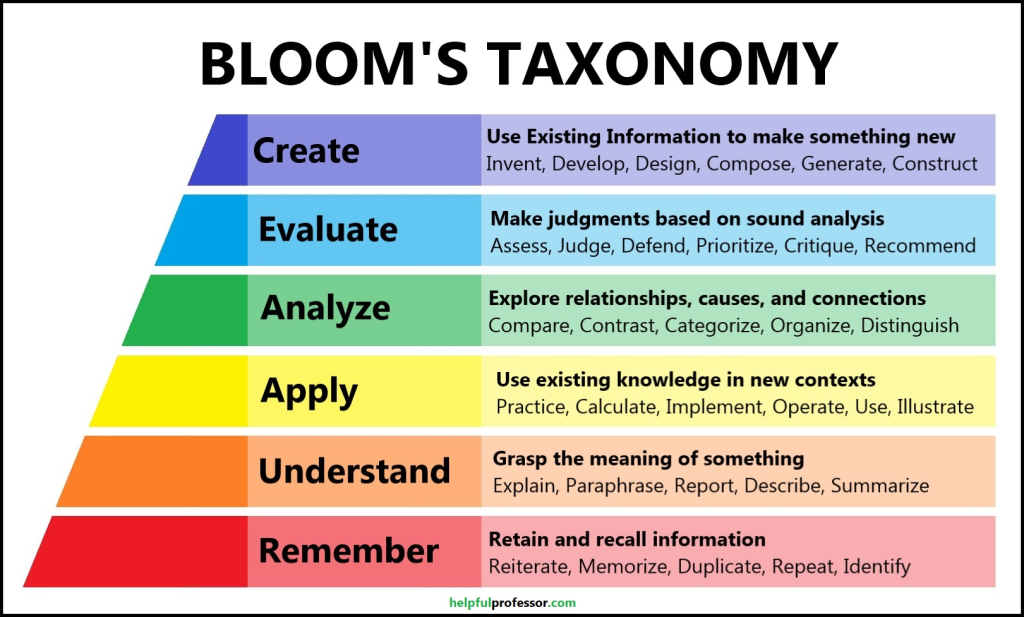

Are you familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy? Originally published in 1956, it became a useful resource that classified learning tasks by level of complexity. The original model was revised in 2001 by a committee of academics in cognitive and educational sciences, with key changes being the use of verbs to describe cognitive process (instead of nouns); the addition of “Create” (rather than “Evaluate”) as the level with highest complexity; and more granular definitions for the cognitive process to allow for clearer differentiation between terms.

In our Assessment Study Group with Prof Pasquini (HEP, Lausanne), we are using the revised taxonomy in an exercise to consider curriculum alignment. This means that we are considering whether (1) we have clear learning goals in a unit planner, (2) we have concrete assessments that allow us to gauge progress towards that goal, (3) we offer variety in our assessment practices that promote higher order thinking skills and metacognitive awareness in our students (also connecting to our Principles of High Quality Learning).

I have been inspired by one of the articles Prof Pasquini gave us to read, which lists a series of different activities under each category, igniting my imagination with ideas for my literature and TOK classes. This led me to consider how I might be able to share these with you. If you are francophone, I invite you to read the original article; otherwise, I will attempt to summarise an English translation below.

Level 1: Remember. The simplest and most basic level of intellectual activity. Tasks at this level require the student to draw knowledge from long-term memory. This level is mainly concerned with factual data. Activities include reciting the multiplication table for a number, naming certain historical events and dates, and recognising the correct answers by circling them or by matching pictures and words.

Level 2: Understand. Tasks at this level require students to demonstrate their understanding by making meaningful connections between what they remember and a new task or learning. Competencies include:

A. Establishing links between what they already know and a new task or a new apprenticeship; for example:

- Underline all the adverbs in this paragraph (or text).

- Write a report on your trip.

B. Giving or finding examples, e.g.:

- Give an example of the heat transfer process in your home.

- Find an example of a work of art that belongs to the cubist movement.

- Find a parallelogram among the images in this magazine.

C. Converting knowledge from one form to another; for example:

- Draw an Egyptian pyramid from the description.

- Translate this paragraph from English into French.

- Draw one of the characters in the story.

- Recite the multiples of eight.

D. Classifying into categories that are already provided and relatively simple, such as:

- Classify these animals as “vertebrates” or “invertebrates”, or “furred”, “feathered” or “finned”.

E. Summing up; for example:

- Summarise the story in your own words.

- Summarise what your partner has said.

- Summarise the main contributions of this man of science.

F. Making simple (factual) predictions, such as:

- What do you think will happen next (in a story)?

- What could happen if we changed this step? this characteristic? this ingredient?

- From what you know about gases, what will be the results of this experiment?

G. Making simple comparisons (mainly factual), e.g.:

- Compare two people, two historical facts, two events, two research discoveries.

- What are the similarities and differences between these two ways of solving this mathematical problem?

H. Explaining simple causes and effects; for example:

- How does a solar panel work?

- What has the character done in this story?

- What is the impact of this action?

- Why did the liquid become solid?

Level 3: Apply. Tasks at this level require students to apply their knowledge or understanding to a practical exercise by transferring a learned procedure to a familiar or unfamiliar task, such as:

- Write a poem in the shape of a diamond

- Use the formula or process we have learned to solve a new problem.

- Give a speech to the class, following the rules you have learnt.

- Demonstrate your ability to present using PowerPoint software.

This level also encompasses simple research processes for finding general and, above all, factual information; for example:

- Find the origin of the cry “Eureka!”.

- Find out more about wolverines.

Level 4: Analyse. This level requires students to break down their knowledge of a given subject into its component parts and to demonstrate the links between the parts and the whole.Competencies include:

A. Recognising the most relevant and important information; for example:

- What are the key arguments in this debate? this article? this novel?

- What are the most significant findings from this survey?

- What are the most important characteristics of this artistic movement? This musical composition?

B. Distinguishing facts from opinions; for example:

- Which statements are facts and which are mere opinions in this article?

C. Discerning the links between ideas, particularly the most complex cause-and-effect relationships; for example:

- What effects does the climate have on people’s lifestyles and behaviour?

- What effects does the sun have on the growth of different plants?

D. Organising the parts of a whole into a system or structure; for example:

- Name in order the main stages in the formation of lightning.

- Present the data from your survey or experiment in the form of a scientific report.

E. Determining the underlying points of view, perspectives, opinions and intentions; for example:

- What are the arguments for and against territorial rights from the point of view of the natives and that of the conquerors?

- What is the intention of the author? the artist? the illustrator?

F. Organising data or information into tables, diagrams, matrices, idea maps or criteria grids, or by using them to analyse; for example:

- Draw an idea map illustrating the genetic and environmental factors that influence children’s development.

- Develop a network of energy-related concepts.

- Compare two psychology models, two writers, two historical events, two wars, using a five-category grid.

G. Listing a number of research projects and organising them in order to resolve certain issues.

The ‘analyse’ level also includes research undertaken with a view to resolving complex issues or difficult situations; for example:

- Conduct research to answer the following questions: what is Erythropoietin (EPO), and why do athletes use it? What else could they do?

- Why is the wolverine described as “the most social of all animals”? Is this accurate?

Level 5: Evaluate. Tasks at this level involve students exercising critical judgement, detecting inappropriate and illogical material, making judgements about the value or ethics of things based on accepted criteria or standards and drawing conclusions, or stating a well-founded reason. They can demonstrate critical thinking by:

A. Detecting falsehoods and inconsistencies; for example:

- Are the historian’s or scientist’s conclusions logical, given the information provided, or are there inconsistencies in the discourse? the history? the argumentation?

B. Identifying the problems that need to be solved; for example:

- What potential problems could overpopulation cause?

- What solutions should be found to this situation? And why?

C. Making an appropriate judgement about the effectiveness or quality of certain products, procedures, arguments, models, theories or conclusions; for example:

- How effective is this diet?

- Rank these arguments from strongest to weakest.

- Assess a work of art, an essay, a presentation or a musical performance using a grid of criteria.

Level 6: Create. This is the most complex and intellectually challenging level. Competencies include:

A. Producing a new or original object, idea, solution or process resulting from a unique approach or a novel combination of elements, where the result must meet pre-specified criteria and the requirements of the task.

B. Drawing up a detailed step-by-step plan for producing an object, a project, a solution to a problem, a research project or an essay. This plan should summarise the most significant elements and the possible options (in some cases, all the possible options). Carry out this plan (not necessarily in all cases); for example:

- Combine the best elements of two games or two sports teams to produce a new game or a new team.

- Combine the characteristic elements of marsupials and monotremes to create a new animal.

- Write a detailed proposal for a technological and structural project, or an important work of visual art.

- Compose a musical score for a film based on a particular book.

- Review the plans for a particular building to turn it into a school.

- Produce a detailed plan and publish a new type of school magazine.

- Develop a detailed plan for a multimedia presentation on environmental issues in our town or region for local audiences.

- Draw up a detailed plan and then write an essay answering the following questions:

- How are global events affecting our economy and what safeguards have our financial institutions put in place to limit the damage?

I have referred to Bloom’s Taxonomy in class, introducing it to my Class 2 students as a way to justify the range of assessments we do in class, and why certain activities are better at introductory stages of a unit, while others are ideal for later in the process. Now I will use it more intentionally in planning my assessments, to think more carefully about how students use their knowledge and skills in more complex ways.

If you choose to explore this taxonomy and find benefits in designing assessments to guide your students through the levels of complexity, please share your experience with me. I would love to know your comments and observations!

Sources

Anderson, Lorin W., David R. Krathwohl, et.al. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman, 2001.

McGrath, Helen and Toni Noble. Gervais Sirois, translator. « Huit façons d’enseigner, d’apprendre et d’évaluer : 200 stratégies utilisant les niveaux taxonomiques des intelligences multiples ». Chenelière Education, 2008.