This summer I read Belonging Through a Culture of Dignity: The Keys to Successful Equity Implementation by Floyd Cobb and John Krownapple (Mimi and Todd Press, 2019). Their thesis resonates with me: schools are misled in thinking that professional development training on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion as topics will make the biggest impact on student wellbeing. Instead, they recommend creating a culture of dignity where every student (and staff member) feels completely welcome and accepted for all aspects of their identity. To accomplish this, the biggest challenge is changing a school culture from valuing achievement to valuing a sense of belonging, which, they underscore, is the basis for achievement.

The authors begin by describing the “Dysfunctional Cycle of Equity Work” they observe at schools. First, an event or other catalyst draws the attention of the school’s direction to the topic of equity. The school makes a public commitment to improving equity, creates a committee that studies the issues and recommends trainings. A training (or a series of trainings) is organised, often with the help of external consultants, which may generate some enthusiasm, but eventually falls short of people’s expectations because they do not see major changes happening, and the school moves on to other pressing goals and equity becomes the “topic” of a training initiative or “just one more thing” they are expected to do from a long list. An additional negative result is that certain diversity trainings (meant to raise awareness of implicit bias, for example) leave participants feeling a sense of blame, shame and guilt.

Pretty sad, right? Well, their conclusion from studying this problem is that the focus should not be on “changing the teachers” but on changing the school culture. They add that “anti-something” programmes/trainings fail (often exacerbating the problem they want to eliminate) because humans respond better to a “positive vision” (“a shared agreement or commitment on which we can focus our energy”) than to a negative one. They propose that positive vision to be creating a culture of dignity, where “everyone feels appreciated, validated, accepted and treated fairly… not by accident but by design”. Members of a school community (students, teachers, staff, parents) feel they belong if they are “respected at a basic level that includes the right to both co-create and make demands on society” (a john. a powell quotation). To support this, they offer a wonderful definition of inclusion:

Inclusion is engagement within a community where the equal worth and inherent dignity of each person is honored. An inclusive community promotes and sustains a sense of belonging; it affirms the talents, beliefs, backgrounds, and ways of living of its members. (p 35)

Most of the book unpacks tools by which to do a self-assessment of the school community and then key ideas to develop what they describe as “dispositions for dignity”, as individuals and as a community.

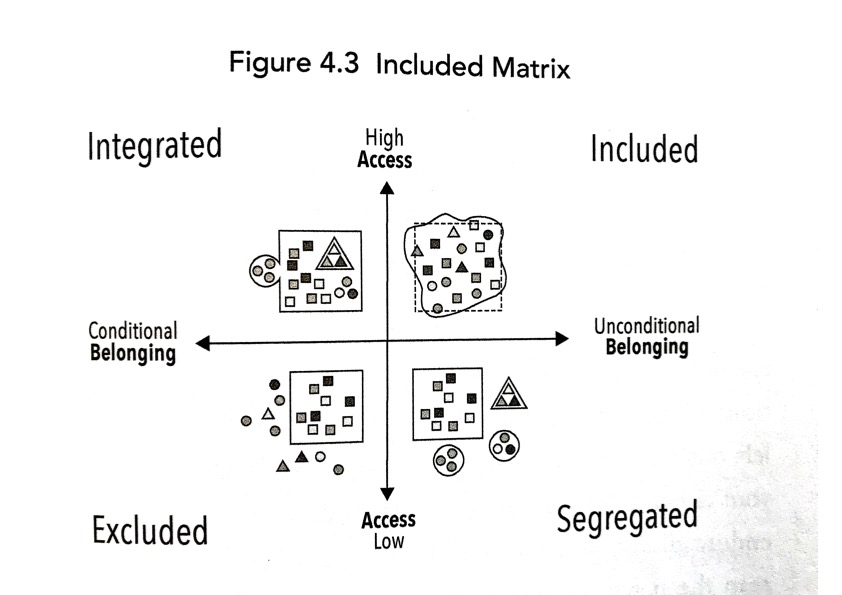

One of the tools I found interesting highlighted the environments within schools based on two conditions: belonging and access. This led to descriptions of four diverse school environments, shown graphically in the diagram and explained in the vocabulary below.

Four Diverse Environments based on Access and Belonging

A. Excluded. People are outside of the culture, denied access because they are unable to meet the membership standards of belonging.

B. Segregated. People are in a subordinate culture, separated from the mainstream culture, where they experience a sense of belonging but proportionally low access.

C. Integrated. People are in the dominant culture, having access but where belonging remains conditional, based on the degree to which people are able to achieve and conform to academic and social standards of the dominant culture.

D. Included. People are of the culture, co-creating and experiencing access and belonging through a process of systemic and cultural transformation.

When I apply this framework to our school, I see elements of the different environments. Our inclusive language (e.g. calling all students Roseans) stands out, as well as the number of surveys and student voice mechanisms operating at the school—these are characteristic of inclusive environments. On the other hand, I can visualise groups of students who are in some ways “segregated” within our school for a perceived “lack” (English fluency, athletic abilities, gender or sexual identity). The diagram also led me to wonder whether students themselves feel “Unconditional belonging” and the range of answers they would provide if we asked them. To that end, beyond the implications at the whole-school level, the diagram raises interesting questions regarding how each individual student may feel, especially whether any student (or teacher) feels they are excluded, segregated or even integrated, but not really “included in co-creating the [Rosey] experience”. Cobb and Krownapple emphasise that when one does not feel their identity is completely embraced, they are forced to negotiate and decide whether they prioritise access or belonging:

If access is more important, you endure discomfort and assaults on your identity until you can reap the perceived benefit of integration. If belonging is more important, you’ll abandon the notion of integration and seek the belonging and safety offered in a segretated environment. (p 72)

What I found poignant in this text was that it raised questions in my mind about the range of identities (or aspects of identity) which I consciously or unconsciously value above others, and to what extent students, teachers and parents contribute to this “ranking” of identity elements. The authors critically adress one specific element: achievement. “We educators live and work in a culture that does not value children for who they are but for what they can achieve. In other words, achievement takes priority over personhood, relationship, community and belonging.” (p 38) They suggest that schools send the message that achievement comes before belonging (that is, that only once you “do well in school”, will you be a valued and respected member of the community) when it should be the other way around: first students feel they belong and are welcome (for who they are, not for what they can do), and then achievement is something they can work towards within this safe environment. I would extend the statement to all teaching staff: all teachers should belong and feel welcome for who they are, so they can then work towards achievement, rather than feeling they have to “prove their worth” in order to be accepted as a member of the community.

Cobb and Krownapple discuss some negative outcomes of a culture that does not honour the whole person with dignity: first is the students’ obsession with grades, (which we have often discussed at Le Rosey but still not solved); second is the “culture of humiliation”, which seeks to alienate others to elevate oneself (again, signalling belonging), and third is the never-ending competition, as if there will be a cut-off point for belonging and we don’t want to be left out of that race. The authors qualify, “If belonging is seen as conditional, it demands compliance, conformity, assimilation, and other forms of compromising one’s personhood” (p 72). I am sure we all agree this is undesirable for any member of our community.

In my next entry, I will unpack more of their toolkit, including ideas on recognising “distortions of dignity”, developing “dispositions for dignity” and shaping a culture of dignity.

Source: Cobb, Floyd Cobb and John Krownapple. Belonging Through a Culture of Dignity: The Keys to Successful Equity Implementation. Mimi and Todd Press, 2019.

Note: The book Belonging Through a Culture of Dignity by Floyd Cobb and John Krownapple is available in the teachers’ Reading Corner in the staff room, Schaub building. Don’t forget to enter your details on the sign-out sheet if you borrow a text. Happy reading!