On Friday 31st May 2024 Institut Le Rosey hosted its third Festival of Education. 50 speakers led sessions on a range of topics including AI, mental health, DEIJ, leadership, cognitive psychology and sustainability. In his opening, Kim Kovacevic (EduFest Director and Director of Academics at our school), highlighted the importance of narrative: creating compelling stories that help us make sense of the world through connections. For me, EduFest was important in helping me create a narrative about the future of education: What is the “compelling story” that we need our students to understand, internalise and respond to?

The session I organised, entitled “Walking the Talk: Embedding Sustainability in Education” was a moderated conversation between Frazer Cairns, Director at the International School Lausanne, and Lee Howell, Executive Director at the Villars Institute. My objective in inviting Dr Cairns and Dr Howell was to highlight the importance of bringing big-picture thinking and new knowledge into the education field, then to consider its practical implications. I wanted to learn actionable recommendations at the macro and micro levels from leaders working directly at those levels, combining conceptual and procedural knowledge with specific experiences.

I am impressed by the sustainability materiality assessment that Dr Cairns is leading at ISL, where the entire community has participated in defining their priorities and large-scale action steps are implemented. Similarly, the whole-village approach from Villars Institute is to be “a platform for systemic change and a place for intergenerational collaboration”, including bringing together 13-19 year olds and adult professionals in their Villars Fellows programme, as well as their systems leadership trainings.

At our session my first guiding question was: What are the key factors that all institutions must take into account to make sustainability efforts successful? Lee Howell began by suggesting that the narrative around sustainability itself has changed in the last 10 years, from a focus on the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the fear of a rise of 1.5°C in temperature, to an understanding of complexity and systems thinking. He suggested we can move from a state of “eco-anxiety” to “eco-ambition” by developing an understanding of systems thinking and a growth mindset, which will generate agency in our young people. He also proposed that the 9 Planetary Boundaries from the Stockholm Resilience Centre provides a framework to analyse the current state of or planet, and that intergenerational, interdisciplinary collaboration will help generate solutions to global problems like food security, loss of biodiversity and climate change. He said we can “fall in love with the challenges”, and I appreciate that approach where the problem itself (not the discipline, not an agenda) drives the search for a solution that naturally brings together different aspects of the issue, different fields or research and different stakeholders.

Frazer Cairns also presented a balanced combination of aspirational, principled mindset and concrete actions. He emphasised the importance of hope and optimism to fuel agency, and that educational institutions should bridge the disconnect between what we teach and how we act as members in this community (and as a collective entity). We already teach “Sharing the planet” units in our programme—our teachers and students are well aware of issues in food scarcity, migration, waste management and non-circular economies. However, we must then reflect carefully on our own institutional operations: to what extent do our operations (energy consumption, waste management, supplies and food purchasing, etc.) contradict those key principles? He also noted that “narratives compete”: the goal for the institution, then, must be to identify which actions will generate the biggest buy-in to create the biggest impact (the 80/20 or Pareto Principle). To achieve this at ISL, Dr Cairns invited stakeholders (teachers, parents, staff and community partners) through different formats to rank priorities from a list. (He said, “People don’t fear change; they fear loss.”) Four key areas that this feedback highlighted were energy, pollution, resources and waste. A concrete action plan around each priority can then be drafted, including how to measure impact for each action step.

I have been thinking that all educational institutions should be shifting their focus to sustainability (isn’t that the most important contribution we can do to the future of our world?): disciplinary content they teach, co-curricular opportunities, professional development, leadership and HR, and business operations (energy, water, waste, transportation, food). Where can we find a blueprint for that? Frazer Cairns created a framework for ISL: a project and implementation process that was customised for the school, which is a work-in-progress that gets reviewed when they hit different benchmarks. In the Americas, UWC Costa Rica has developed its own Sustainability Framework with community input, in order to meet its need to rethink sustainability practices as the strategic goal for the school. In both cases they have sought to marry environmental (what is best for the planet) and human (what is best for the members of the community) factors. I appreciate this approach, which reminds me of Kate Raworth’s model, presented in Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.

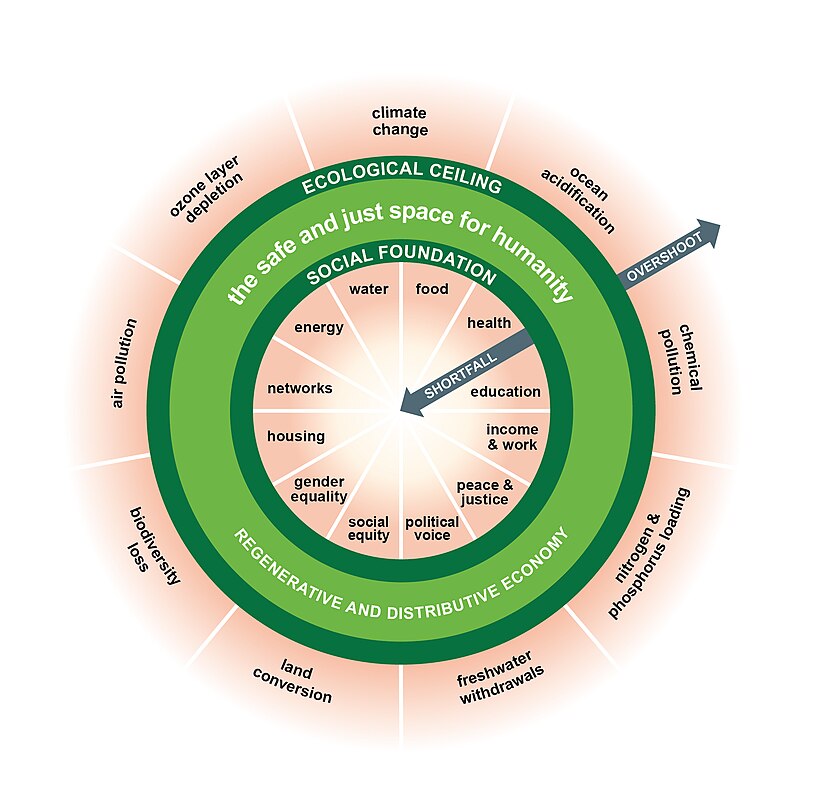

As her model shows, Raworth proposes that we work simultaneously on two different dimensions: not overshooting the “Ecological Ceiling” (the same 9 planetary boundaries from the Stockholm Resilience Centre) and not falling short of the “Social Foundation”. As she claims, we must work within a “safe and just space for humanity” so that both the planet and humans can thrive.

Would this model apply to schools? If we extend the model to our school community… I think yes. If we wanted to ensure that Le Rosey thrives “within the doughnut”, we’d need to ask questions regarding procurement and the production of the food, supplies and materials we purchase, as they may contribute to land conversion and diversity loss, nitrogen & phosphorus loading, etc. We’d also need to ask whether our own school promotes or guarantees gender equality, social equity, or perhaps how we contribute to peace & justice within our community and beyond. One of Raworth’s most compelling propositions is that businesses move beyond a net-zero model to a generous model: not only should we not generate waste, but we could create something to be utilised by others, be it extra energy through our solar panels, extra produce from our gardens, extra oxygen by planting more trees, or extra hours of community service through local school projects. This would ensure that our community thrives without crossing environmental or human boundaries for safety and justice.