It is now almost a year that I have been working as Professional Development Coordinator at my school, and during this time I have had the opportunity to put into place initiatives like a format for teacher-led “Show and Tell” events, collaborative networks, one-on-one meetings, and classroom observations. My current project is putting together a three-day professional development conference on a boat, like a curriculum-centred staff retreat. I have a long “to-do list” after that event, but I also believe that meaningful change cannot happen overnight and I am wary of “project fatigue”, so I tread lightly.

Despite my “light treading”, initiatives are nevertheless met with resistance: some colleagues might not want to present in front of the faculty; a few don’t want to be observed/visited; others may not want their holiday schedule to change; a couple are not interested in working with other departments to review a class syllabus; some say nobody in the school can “teach them anything useful”; etc.

As I reflect on the variety of arguments against our PD initiatives, I have come to believe that the resistance is not to a specific initiative or event per se (or to me or my position), but rather to change in our school structure and atmosphere– change is visible, palpable at our school now, and this is naturally unsettling. Resistance to change is natural and normal (anyone read Who Moved My Cheese?) and there are ways to deal with change, some of which I am considering at this moment.

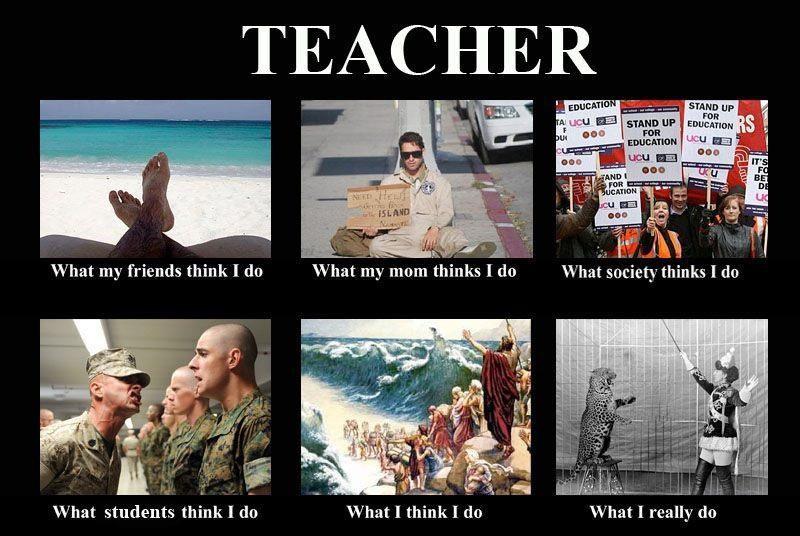

However, there is another point I wish to make beyond “change is naturally unsettling”, and it is that I think there is a difference between those who jump at a new initiative and those who are more reluctant. I believe that an important component of this reaction has to do with our own individual understanding of what it means to be a teacher.

In my opinion, there is a tension between those who have a core belief that teaching involves a single set of practices and those who believe that it is an extremely complex set of practices. The first group happily works within the confines of “one’s own classroom”, where we close the door and are, in a way, “masters” of our space, the content we provide, and the knowledge generated within. If we envision teaching as supporting our students in acquiring content knowledge, then it is clear that the most important professional development for us will be to become masters of our discipline. In this case, school-wide trainings seem unnecessary and will not bring us closer to our professional goals. We must dedicate our time, resources and effort to stay up-to-date on in the scholarly development of our chosen subject area, or the academic programme we deliver.

The second group works with a different model. We believe that as a teacher it is our responsibility to do many things at once– yes, we need to be knowledgeable in our discipline, but we also see the teaching craft as a practice that requires constant professional development. Further, we believe that understanding our students, their needs, their learning styles, is a permanent project that demands studies in the field of education and often in many other fields. We believe that teaching involves being agents of our students’ development beyond content knowledge– we become models of how to be an internationally-minded citizen, how to live productively in another country, how to relate to others in positive ways, how to develop self-discipline and other healthy habits, how to be a scholar who is ethical and honest and engaged and caring. There is so much to be involved in that to do it well we have to keep reading and reflecting on a million different tasks. Teaching content is just one fragment of our responsibility as an educator.

As you can imagine, I feel closer to this second group. Perhaps the image I have of being a teacher is shaped by my understanding of this profession as one of service. If my goal is to serve my students best, then it follows that I must train myself to be better in what they need– yes, content, but also habits of mind, approaches to academic work, variety in teaching and learning styles, and a host of other interwoven competencies that can help me manage the different hats I might wear (teacher, boarding staff, faculty advisor for a club, after-school activity supervisor, academic tutor etc.) In that case, training in PSHE, pastoral care, multiple intelligences, use of technology, brain-based learning, team teaching, visual learning techniques… all become desirable channels to provide a better service to my students. Yes, the number of areas I must explore to become a better educator multiply, but that’s a good thing! It moves me away from the self-indulgence of my subject area, and it gives me the opportunity to empathise with my students who also juggle different areas of knowledge on a daily basis.

I would like the opportunity to explore these “teaching models” with my colleagues, but worry that it would be difficult to clearly convey the purpose of such an activity. Should we instead accept that we come from different expectations and move forward, or try to develop the same “teaching model” for all, so that changes will generate less resistance? If we all shared in our definition of what it means to be a teacher, would we all agree on the value of school-wide professional development?

It is now almost a year that I have been working as Professional Development Coordinator at my school, and during this time I have had the opportunity to put into place initiatives like a format for teacher-led “Show and Tell” events, collaborative networks, one-on-one meetings, and classroom observations. My current project is putting together a three-day professional development conference on a boat, like a curriculum-centred staff retreat. I have a long “to-do list” after that event, but I also believe that meaningful change cannot happen overnight and I am wary of “project fatigue”, so I tread lightly.

Despite my “light treading”, initiatives are nevertheless met with resistance: some colleagues might not want to present in front of the faculty; a few don’t want to be observed/visited; others may not want their holiday schedule to change; a couple are not interested in working with other departments to review a class syllabus; some say nobody in the school can “teach them anything useful”; etc.

As I reflect on the variety of arguments against our PD initiatives, I have come to believe that the resistance is not to a specific initiative or event per se (or to me or my position), but rather to change in our school structure and atmosphere– change is visible, palpable at our school now, and this is naturally unsettling. Resistance to change is natural and normal (anyone read Who Moved My Cheese?) and there are ways to deal with change, some of which I am considering at this moment.

However, there is another point I wish to make beyond “change is naturally unsettling”, and it is that I think there is a difference between those who jump at a new initiative and those who are more reluctant. I believe that an important component of this reaction has to do with our own individual understanding of what it means to be a teacher.

In my opinion, there is a tension between those who have a core belief that teaching involves a single set of practices and those who believe that it is an extremely complex set of practices. The first group happily works within the confines of “one’s own classroom”, where we close the door and are, in a way, “masters” of our space, the content we provide, and the knowledge generated within. If we envision teaching as supporting our students in acquiring content knowledge, then it is clear that the most important professional development for us will be to become masters of our discipline. In this case, school-wide trainings seem unnecessary and will not bring us closer to our professional goals. We must dedicate our time, resources and effort to stay up-to-date on in the scholarly development of our chosen subject area, or the academic programme we deliver.

The second group works with a different model. We believe that as a teacher it is our responsibility to do many things at once– yes, we need to be knowledgeable in our discipline, but we also see the teaching craft as a practice that requires constant professional development. Further, we believe that understanding our students, their needs, their learning styles, is a permanent project that demands studies in the field of education and often in many other fields. We believe that teaching involves being agents of our students’ development beyond content knowledge– we become models of how to be an internationally-minded citizen, how to live productively in another country, how to relate to others in positive ways, how to develop self-discipline and other healthy habits, how to be a scholar who is ethical and honest and engaged and caring. There is so much to be involved in that to do it well we have to keep reading and reflecting on a million different tasks. Teaching content is just one fragment of our responsibility as an educator.

As you can imagine, I feel closer to this second group. Perhaps the image I have of being a teacher is shaped by my understanding of this profession as one of service. If my goal is to serve my students best, then it follows that I must train myself to be better in what they need– yes, content, but also habits of mind, approaches to academic work, variety in teaching and learning styles, and a host of other interwoven competencies that can help me manage the different hats I might wear (teacher, boarding staff, faculty advisor for a club, after-school activity supervisor, academic tutor etc.) In that case, training in PSHE, pastoral care, multiple intelligences, use of technology, brain-based learning, team teaching, visual learning techniques… all become desirable channels to provide a better service to my students. Yes, the number of areas I must explore to become a better educator multiply, but that’s a good thing! It moves me away from the self-indulgence of my subject area, and it gives me the opportunity to empathise with my students who also juggle different areas of knowledge on a daily basis.

I would like the opportunity to explore these “teaching models” with my colleagues, but worry that it would be difficult to clearly convey the purpose of such an activity. Should we instead accept that we come from different expectations and move forward, or try to develop the same “teaching model” for all, so that changes will generate less resistance? If we all shared in our definition of what it means to be a teacher, would we all agree on the value of school-wide professional development?